Well, after many, many suggestions on how my list of dystopian franchises could be augmented – this mainly consisted of poeple asking me “what about (blank)?” – I decided there were a few that I really couldn’t proceed without mentioning. This will be my last tour of the dystopia factory, lord knows that place gets depressing after awhile! But one thing at a time. Here’s my final installment in dystopian science fiction series, a hybrid list of novels, graphic novels, and movies!

A Clockwork Orange:

This dystopian novella was originally written in 1962 and was adapted into film by the great Kubrick almost a decade later. In addition, it was adapted into play after the author realized he didn’t like how the adapted movie ended. Having experienced all three, I can tell you that the movie was probably the best. In addition to the rather ingenious ideas presented by Anthony Burgess, it also benefited from Kubrick’s directorial genius and the superb acting of Malcolm McDowell.

This dystopian novella was originally written in 1962 and was adapted into film by the great Kubrick almost a decade later. In addition, it was adapted into play after the author realized he didn’t like how the adapted movie ended. Having experienced all three, I can tell you that the movie was probably the best. In addition to the rather ingenious ideas presented by Anthony Burgess, it also benefited from Kubrick’s directorial genius and the superb acting of Malcolm McDowell.

Set in the not-too-distant future, the story revolves around a British youth named Alex who is growing up in a world permeated by youth violence. He is the leader of a group of thugs known as “The Droogs”, young men who go about committing acts of “ultra-violence” which consists of them beating up homeless people, random strangers and other gangs, as well as committing theft and gang rape.

Set in the not-too-distant future, the story revolves around a British youth named Alex who is growing up in a world permeated by youth violence. He is the leader of a group of thugs known as “The Droogs”, young men who go about committing acts of “ultra-violence” which consists of them beating up homeless people, random strangers and other gangs, as well as committing theft and gang rape.

In time, Alex and his friends go to far (even for them!) and an innocent woman is murdered during a break-in. His friends, who are already angry over his bullying and strong arming of them, decide to betray him and leave him to the police. Once in prison, Alex decides to cut his sentence short by undergoing a radical government experiment – an artificially created conscience through Pavlovian conditioning!

The result of this conditioning is that Alex is no longer capable of committing any acts of violence. In fact, even the mere thought of violence produces a reaction so strong that he breaks down and is overwhelmed by nausea. This renders him benign, but also helpless. And in time, all his past crimes begin to catch up with him and he is nearly killed. Once he wakes up in the hospital, he discovers the conditioning has worn off, and he can either resume his old ways, or strike out on a new path…

Another interesting side effect of the conditioning is that he can no longer listen to Beethoven without getting sick either. This has to be one of the most curious and intriguing scenes in the movie, where a restrained and helpless Alex begs the doctors to turn off the symphony because he can’t stand the idea of not being able to listen to it. Much like everything else he does, it speaks volumes of his sociopathic nature.

Ultimately, the movie differed from the novel in that the final chapter was omitted. Immediately before this, we see how Alex is now freed from the conditioning. He also seems intent on blaming the current government, which will oust them from power. But beyond that it not quite clear what’s going to happen. However, the following chapter shows how Alex has realized, independently, that he doesn’t want to live a life of violence anymore. Human freedom, he’s determined, is the ability to make choices for oneself, free of persuasion and operate conditioning.

As I said, I truly think the movie was an improvement on the novel, which is a rare thing with adaptations. Still, it is was in the film that the point of the story really came through, thanks to Kubrick’s usual attention to detail and subtlety. Whether it was through those long, close-up shots of McDowell and his crazy eyes, the combination of wide angle action shots in slow motion, or the way that it played to the tune of Beethoven, you really got a sense of the odd combination of genius and madness that is the anti-hero Alex. The reliance on white, sterile settings also helped to punctuate the sociopathic nature of the story – how underneath the veneer of domesticity, brutality and violence can exist! And last, by leaving the ending a mystery, the moral was more ambiguous, which made for a far more effective dystopian feel!

A Scanner Darkly:

Next up, we have Philip K Dicks seminal novel about drug abuse, self-destruction and the various hypocrisies arising out of America’s war on drugs. In this near-future scenario, which takes place in California in 1994 (seventeen years after it was written), a new drug has hit the streets known as Substance D – or SD, which stands for Slow Death. This powerful hallucinogenic is a great high, is violently addictive, and can render users brain damaged after too much use and abuse. And as a result of its popularity and impact, society is gradually becoming a full-blown police state, where cameras – or “Scanners” – are on every street corner and in the home of every suspected dealer.

Next up, we have Philip K Dicks seminal novel about drug abuse, self-destruction and the various hypocrisies arising out of America’s war on drugs. In this near-future scenario, which takes place in California in 1994 (seventeen years after it was written), a new drug has hit the streets known as Substance D – or SD, which stands for Slow Death. This powerful hallucinogenic is a great high, is violently addictive, and can render users brain damaged after too much use and abuse. And as a result of its popularity and impact, society is gradually becoming a full-blown police state, where cameras – or “Scanners” – are on every street corner and in the home of every suspected dealer.

Written from the point of view of an undercover narcotics agent, the story follows his descent into addiction and his eventual inability to tell reality from fantasy. Through repeated use of Substance D, he gradually becomes brain damaged himself, is released from the police department, and must go to a privately run recovery-center known as “New-Path”. There, he discovers that these centers, which operate like franchises, are actually growing the plant that Substance D is synthesized from. An interesting twist in which we learn that the people profiting from the side effects are the one’s providing the drugs. A stab at strong-arm governments or the pharmaceuticals industry, perhaps?

Written from the point of view of an undercover narcotics agent, the story follows his descent into addiction and his eventual inability to tell reality from fantasy. Through repeated use of Substance D, he gradually becomes brain damaged himself, is released from the police department, and must go to a privately run recovery-center known as “New-Path”. There, he discovers that these centers, which operate like franchises, are actually growing the plant that Substance D is synthesized from. An interesting twist in which we learn that the people profiting from the side effects are the one’s providing the drugs. A stab at strong-arm governments or the pharmaceuticals industry, perhaps?

For the sake of adapting the movie to film, director Richard Linklater shot the entire thing digitally and then had it animated through the use of interpolated rotoscope. The effect of this was to render every single image in a vivid, almost cartoon-like format, which could only be interpreted as an attempt to mimic the effects of hallucinogens. This animation also came in handy with the rendering of the “scramble suit”, a sort of cloak-like device that PKD invented to ensure that undercover agents in his story could completely disguise their appearance, voice, and any other identifying characteristics.

In addition to being science fiction genius, these cloaks were a clear allegory to the anonymity of undercover agents and a faceless system of justice. While responsible for infiltrating and busting up the narcotics subculture, PKD clearly understood that this sort of profession can lead to an identity crisis, especially if the agents in question find themselves using drugs and becoming over-sympathetic to the people they are spying on. This, of course, is precisely what happens to the main character in the story!

In addition to being science fiction genius, these cloaks were a clear allegory to the anonymity of undercover agents and a faceless system of justice. While responsible for infiltrating and busting up the narcotics subculture, PKD clearly understood that this sort of profession can lead to an identity crisis, especially if the agents in question find themselves using drugs and becoming over-sympathetic to the people they are spying on. This, of course, is precisely what happens to the main character in the story!

In short, the novel was a commentary on the dangers of recreational drug use, but also on the reasons for why such subcultures come into existence in the first place. In addition to ruining lives and causing crime, repression, domestic surveillance, and other extra-legal practices can become quite commonplace. All of this mirrored PKD’s own experiences with the drug subculture and the law, which is why he dedicated the book to all the friends he had who succumbed to drug abuse and died as a result. Very sad!

And let’s not forget the name, a play on the words from the Biblical passage, 1 Corinthians 13:12 : “Through a mirror darkly.” In this day and age, where “scanners” are the means for monitoring society and police officers spend hours looking at their feeds, the scanner has become a sort of means through which people attempt to gaze into other peoples’ souls. But, as with the Biblical passage, this title is meant to refer to how, when we look at the problems of drug use in our society, we are seeing it all through a haze, the result of our own prejudices and preconceptions.

Akira:

How the hell did I forget this one last time? I mean seriously, this is one of my favorite movies and one of the most inspired Mangas of all time! Not only that, it’s a pretty good example of a dystopian franchise. And yet, I forgot it! WHAT THE HELL WAS I THINKING?! But enough self-flagellation, I came here to talk about Akira! So, here goes…

How the hell did I forget this one last time? I mean seriously, this is one of my favorite movies and one of the most inspired Mangas of all time! Not only that, it’s a pretty good example of a dystopian franchise. And yet, I forgot it! WHAT THE HELL WAS I THINKING?! But enough self-flagellation, I came here to talk about Akira! So, here goes…

In 1988, famed Japanese writer, director and comic book creator Katsuhiro Otomo undertook the rather monumental task of adapting his Manga series Akira to the big screen. Though some predicted that a two hour movie could never do justice to the six-volume series he had written, most fans were pretty pleased with the end product. And the critical response was quite favorable as well, with the film being credited for its intense visualizations, cyberpunk theme, its post-apocalyptic feel, and the exploration of some rather heavy existential questions.

To break it down succinctly, Akira takes place in Neo-Tokyo, a massive urban center that was literally build up from the ruins of the original. According to the story’s background, WWIII took place in 1989, and after twenty years of rebuilding, the world once again appears to be one the brink. However, as we come to learn, the destruction of Tokyo was not the result of the nuclear holocaust per se. It’s destruction merely heralded it in after the world witnessed the city’s obliteration, assumed it to have been the result of a nuclear attack, and starting shooting their missiles at each other. The real cause was a phenomena known as “Akira”, an evolutionary leap that scientists had been studying and lost control of…

To break it down succinctly, Akira takes place in Neo-Tokyo, a massive urban center that was literally build up from the ruins of the original. According to the story’s background, WWIII took place in 1989, and after twenty years of rebuilding, the world once again appears to be one the brink. However, as we come to learn, the destruction of Tokyo was not the result of the nuclear holocaust per se. It’s destruction merely heralded it in after the world witnessed the city’s obliteration, assumed it to have been the result of a nuclear attack, and starting shooting their missiles at each other. The real cause was a phenomena known as “Akira”, an evolutionary leap that scientists had been studying and lost control of…

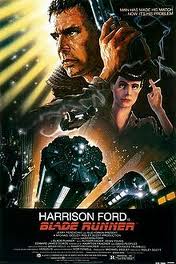

Quite the story, but what I loved most about the adapted movie and the manga on which it was based was the level of detail. Set in 2019 (the same year as Blade Runner, coincidentally!) this series incorporated a lot of concepts which made for a far more intricate and interesting tale. First off, there’s the concept of a post-apocalyptic generation that is filled with unrest and angst, having grown up in a world permeated by the horrors of nuclear war. Second, there’s the ever-present element of gang warfare that has sprung up amidst the social decay. Third, there’s a government slouching towards dictatorship in response to all the protests, unrest and chaos that is consuming the city.

Quite the story, but what I loved most about the adapted movie and the manga on which it was based was the level of detail. Set in 2019 (the same year as Blade Runner, coincidentally!) this series incorporated a lot of concepts which made for a far more intricate and interesting tale. First off, there’s the concept of a post-apocalyptic generation that is filled with unrest and angst, having grown up in a world permeated by the horrors of nuclear war. Second, there’s the ever-present element of gang warfare that has sprung up amidst the social decay. Third, there’s a government slouching towards dictatorship in response to all the protests, unrest and chaos that is consuming the city.

Into all this, you get a secret military project in which the Akira phenomena is once again being studied. Though motivated by a desire to control it and prevent what happened last time from happening again, it seems that history is destined to repeat itself. Once again, the survivors must crawl from the wreckage and rebuild, their only hope being that somehow, they will get it right next time… A genuine dystopian commentary if ever I heard one!

But what was also so awesome about the series, at least to me, was the underlying sense of realism and tension. You really got the sense that Otomo was tapping into the Zeitgeist with this one, relating how after decades of rebuilding through hard work and conformity, Japan was on the verge of some kind of social transformation. Much like in real life, the characters of the story have been through a nuclear holocaust and have had to crawl their way back from the brink, and a sense of “awakening” is one everybody’s lips and they are just waiting for it to manifest.

But what was also so awesome about the series, at least to me, was the underlying sense of realism and tension. You really got the sense that Otomo was tapping into the Zeitgeist with this one, relating how after decades of rebuilding through hard work and conformity, Japan was on the verge of some kind of social transformation. Much like in real life, the characters of the story have been through a nuclear holocaust and have had to crawl their way back from the brink, and a sense of “awakening” is one everybody’s lips and they are just waiting for it to manifest.

A clear allusion to post-war Japan where the country had been bombed to cinders and was left shattered and confused! Not to the mention the post-war sense of uniformity where politicians, corporations and Zaibatsu did their best to repress the youth movements and demands for social reform. Well, that was my impression at any rate, others have their own. But that’s another thing that worked so well about Akira. It is multi- layered and highly abstract, relying on background, visuals and settings to tell the story rather than mere dialogue. In many ways, it calls to mind such classics as 2001, Clockwork Orange, and other Kubrick masterpieces.

Children of Men:

Made famous by the 2006 adaptation starring Clive Owen, this dystopian science fiction story was originally written by author P.D. James in 1992. The movie was only loosely based on the original text, but most of the particulars remained the same. Set in Britain during the early 21st century, the story takes place in a world where several subsequent generations have suffered from infertility and population growth has dropped down to zero. The current generation, the last to be born, are known as “Omegas” and are a lost people.

Made famous by the 2006 adaptation starring Clive Owen, this dystopian science fiction story was originally written by author P.D. James in 1992. The movie was only loosely based on the original text, but most of the particulars remained the same. Set in Britain during the early 21st century, the story takes place in a world where several subsequent generations have suffered from infertility and population growth has dropped down to zero. The current generation, the last to be born, are known as “Omegas” and are a lost people.

What’s more, the growing chaos of the outside world has also led to the creation of a dictatorial government at home. This is due largely to the fact that people have lost all interest in politics, but also because the outside world has become chaotic due to the infertility crisis. Much like in V for Vendetta, the concept of “Lifeboat Britain” makes an appearance in this story and acts as one of the main driving forces for the plot.

In any case, this also leads to the birth of a resistance which wants to end the governments tyrannical control over society, and which comes to involve the main character and his closest friends. In time, the plot comes to revolve around a single woman who is apparently pregnant. Whereas some of the rebels want to smuggle her out of Britain and hand her over to the international Human Project, others want to use her as a pawn in their war against the government. It thus falls to the main character to smuggle her out, protecting her from resistance fighters and the military alike.

In any case, this also leads to the birth of a resistance which wants to end the governments tyrannical control over society, and which comes to involve the main character and his closest friends. In time, the plot comes to revolve around a single woman who is apparently pregnant. Whereas some of the rebels want to smuggle her out of Britain and hand her over to the international Human Project, others want to use her as a pawn in their war against the government. It thus falls to the main character to smuggle her out, protecting her from resistance fighters and the military alike.

Naturally, the movie drew on all the novels strongest points, showing how society had effectively decayed once childbirth effectively ended. It also portrayed the consequences of impending extinction very well – chaos, withdrawal, tyranny, etc. However, when it came time to adapt it to the screen, Mexican film director Alfonso Cuaron (who brought us such hits as A Little Princess, Y Tu Mama Tambien, and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban), also used a variety of visual techniques and sets to convey the right mood.

For example, most of the sets were designed to look like near-future versions of today. In Cuaron’s estimation, all technological progress would have ceased once the implications of the crisis had fully hit, hence all cars, structures, weapons and gadgets were only slightly altered, or used sans modification. So while the billboards, newspapers and signs were all updated and carried messages appropriate for the period, cars, guns and other assorted background pieces looked entirely familiar.

For example, most of the sets were designed to look like near-future versions of today. In Cuaron’s estimation, all technological progress would have ceased once the implications of the crisis had fully hit, hence all cars, structures, weapons and gadgets were only slightly altered, or used sans modification. So while the billboards, newspapers and signs were all updated and carried messages appropriate for the period, cars, guns and other assorted background pieces looked entirely familiar.

In addition, much of the movie is shot in such a way so that the images are grey and the light effect seems piercing. This conveys a general mood of drab sadness, which is very accurate considering the setting! Last, Cuaron and his camera crews made many continuous action shots using wide angle lenses in order to capture a sense of crisis and how it effected so many people. Never was there a sequence in which you only saw the main actors and their immediate surroundings. The focus, like the scope of the story, was big and far-reaching.

Ghost in the Shell:

Much like Akira, this franchise comes to us by way of Japan and is cyberpunk-themed. In addition, it also came in the form of a manga, then onto a film, but with a television series to follow. And in many respects, it qualifies as dystopian, given that it took place in a dark future where technology has forever blurred the line between what is real and what is artificial. In addition, it also tapped into several cyberpunk trends which would prove to be quite apt (i.e. cyberspace).

Much like Akira, this franchise comes to us by way of Japan and is cyberpunk-themed. In addition, it also came in the form of a manga, then onto a film, but with a television series to follow. And in many respects, it qualifies as dystopian, given that it took place in a dark future where technology has forever blurred the line between what is real and what is artificial. In addition, it also tapped into several cyberpunk trends which would prove to be quite apt (i.e. cyberspace).

Again, this story takes place in Japan in the early 21st century, a time when cybernetic enhancements and technological progress have seriously altered society. The main character is named Motoko Kusanagi, a member of a covert operations division of the Japanese National Public Safety Commission known as Section 9. She is affectionately known as “Major” given her previous position with the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. And did I mention she’s a cyborg? Yes, aside from her brain and parts of her spinal cord, she is almost entirely machine, and this plays into the story quite often.

Again, this story takes place in Japan in the early 21st century, a time when cybernetic enhancements and technological progress have seriously altered society. The main character is named Motoko Kusanagi, a member of a covert operations division of the Japanese National Public Safety Commission known as Section 9. She is affectionately known as “Major” given her previous position with the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. And did I mention she’s a cyborg? Yes, aside from her brain and parts of her spinal cord, she is almost entirely machine, and this plays into the story quite often.

In addition to facing external threats, Kusanagi and her companions also face conflicts that arise out of their own nature. These deal largely with issues relating to their own humanity, whether or not a person and their memories can even be considered real anymore if they have been replaced by digital or cybernetic enhancements. These questions were explored in depth in the movie, where events revolve around a sentient program that was developed by the government, but which has since gone rogue and is seeking an independent existence.

In addition to facing external threats, Kusanagi and her companions also face conflicts that arise out of their own nature. These deal largely with issues relating to their own humanity, whether or not a person and their memories can even be considered real anymore if they have been replaced by digital or cybernetic enhancements. These questions were explored in depth in the movie, where events revolve around a sentient program that was developed by the government, but which has since gone rogue and is seeking an independent existence.

However, another thing that makes Ghost in the Shell a possible candidate for the category of dystopia is the setting. Whether it was the manga, the movie, or the television series, the look and feel of the world in which it takes place is quite telling. Always there is a dirty, gritty, and artificial quality to it all, calling to mind The Sprawl, Mega City One, and Neo-Tokyo.

However, another thing that makes Ghost in the Shell a possible candidate for the category of dystopia is the setting. Whether it was the manga, the movie, or the television series, the look and feel of the world in which it takes place is quite telling. Always there is a dirty, gritty, and artificial quality to it all, calling to mind The Sprawl, Mega City One, and Neo-Tokyo.

As in these settings, things look futuristic, but also rustic, poor and improvised, hinting at extensive overcrowding and poverty amidst all the advanced technology. This is a central element to cyberpunk, or so I’m told. In addition to being futuristic, it also anticipates dystopia, being of the opinion that this “advancement” has come at quite a cost in human terms.

Logan’s Run:

Considered by many to be a classic dystopian story, Logan’s Run takes place in a 22st century society where age and consumption are strictly curtailed to ensure that a population explosion – like the one experience in the year 2000 – never happens again. In addition, society is controlled by a computer that runs the global infrastructure and makes sure that the all the dictates of population and age control are obeyed.

Considered by many to be a classic dystopian story, Logan’s Run takes place in a 22st century society where age and consumption are strictly curtailed to ensure that a population explosion – like the one experience in the year 2000 – never happens again. In addition, society is controlled by a computer that runs the global infrastructure and makes sure that the all the dictates of population and age control are obeyed.

In any case, the story revolves around this concept of an age ceiling, where people are monitored by a “palm flower” that changes color every seven years. When they reach 21 – on a person’s Lastday – the crystal turns black and they are expected to report to a “Sleepshop” where they will be executed. Those who refuse to perform this final duty are known as “Runners”, and it falls to “Deep Sleep Operatives” (aka. Sandmen) to track down and terminate these people.

In any case, the story revolves around this concept of an age ceiling, where people are monitored by a “palm flower” that changes color every seven years. When they reach 21 – on a person’s Lastday – the crystal turns black and they are expected to report to a “Sleepshop” where they will be executed. Those who refuse to perform this final duty are known as “Runners”, and it falls to “Deep Sleep Operatives” (aka. Sandmen) to track down and terminate these people.

The main character – Logan 3 – is one such operative. On his own Lastday, he is charged with infiltrated the underground railroad of Runners and finding the place they call “Sanctuary”. This is a place where they are able to live out their lives without having to worry about society’s dictates and controls. However, in time, Logan comes to sympathize with these people, due largely to the influence of a woman named Jessica 6. In the end, the two make plans to escape together for Sanctuary, which turns out to be a colony on Mars.

Right off the bat, some additional elements can be seen here. In addition to the concepts of Malthusian controls and ageism, there is also the timeless commentary on how rationalization and regimentation can lead to inhumanity and repression. Much like in We or Anthem (by Ayn Rand), people do not have names as much as designations. All life is monitored and controlled by a central computer, and it is made clear towards the end that the computer is in fact breaking down. I can remember this last theme appearing in an episode of Star Trek TNG, where a planet of advanced people are beginning to die off because their “Custodian” is malfunctioning and no one knows how to fix it.

Right off the bat, some additional elements can be seen here. In addition to the concepts of Malthusian controls and ageism, there is also the timeless commentary on how rationalization and regimentation can lead to inhumanity and repression. Much like in We or Anthem (by Ayn Rand), people do not have names as much as designations. All life is monitored and controlled by a central computer, and it is made clear towards the end that the computer is in fact breaking down. I can remember this last theme appearing in an episode of Star Trek TNG, where a planet of advanced people are beginning to die off because their “Custodian” is malfunctioning and no one knows how to fix it.

Metropolis:

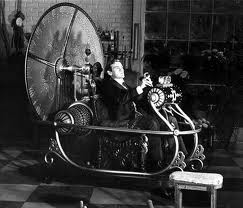

A true classic of both film and expressionist art, this movie also has the added (and perhaps dubious) honor of being a classic of dystopian science fiction! Created in Weimar Germany in 1927 by Fritz Lang, this movie tells the story of a dystopian future where society is ruled by elites who live in vast tower complexes and the workers lives in the recesses of the city far below them where they operate the machinery that powers it all.

A true classic of both film and expressionist art, this movie also has the added (and perhaps dubious) honor of being a classic of dystopian science fiction! Created in Weimar Germany in 1927 by Fritz Lang, this movie tells the story of a dystopian future where society is ruled by elites who live in vast tower complexes and the workers lives in the recesses of the city far below them where they operate the machinery that powers it all.

This physical divide serves to mirror the main focus of the story, which is on class distinction and the gap between rich and poor. To illustrate this artistic vision, director Fritz Lang relied on a combination of Gothic, classical, modern and even Biblical architecture. In an interview, Fritz claimed that his choices for the set design were based largely on his first trip to New York where he witnessed skyscrapers for the first time. In addition, the central building of the futuristic city was based on Brueghel’s 1563 painting of the Tower of Babel (right>).

This physical divide serves to mirror the main focus of the story, which is on class distinction and the gap between rich and poor. To illustrate this artistic vision, director Fritz Lang relied on a combination of Gothic, classical, modern and even Biblical architecture. In an interview, Fritz claimed that his choices for the set design were based largely on his first trip to New York where he witnessed skyscrapers for the first time. In addition, the central building of the futuristic city was based on Brueghel’s 1563 painting of the Tower of Babel (right>).

The theme of class conflict is further illustrated by the fact that the workers who live in the bowels of the city are also responsible for maintaining the machinery that makes the city run. One is immediately reminded of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine and the divide between the Morlocks and the Eloi. This comes through even more when the workers decide to revolt and begin ransacking the neighborhoods of the elites. Ultimately, it is only through the love of the two main characters – Freder and Mariah – that the gulf between the two is sealed and order is restored, a fitting commentary on how society must come together in order to survive and achieve social justice.

In another act of blatant symbolism, we learn early on in the movie that the workers have taken to congregating in a series of tunnels that run under the city. It is here that they meet with Maria, their inspirational leader, and makes plans to change society. So in addition to tall, Babel-like buildings illustrated the gap between rich and poor, we have workers who are literally meeting underground! Wow…

In another act of blatant symbolism, we learn early on in the movie that the workers have taken to congregating in a series of tunnels that run under the city. It is here that they meet with Maria, their inspirational leader, and makes plans to change society. So in addition to tall, Babel-like buildings illustrated the gap between rich and poor, we have workers who are literally meeting underground! Wow…

In addition, several other dystopian elements weave their way into the story. The line between artifice and reality also makes an appearance in the form of the robot which the movie is best known for. This robot was created by Rotwang, a scientist who is in the service of the main character’s father – Joh Fredersen, the master of the city. Apparently, this robot is able to take human form and was created to replace his late wife. Once this robot was released into the city, she began sowing chaos amongst men who begin to lust after her, and is the very reason the workers began revolting in the first place. She even causes the character of Rotwang to go insane when he can no longer distinguish between the robot and the woman she’s impersonating.

In addition, several other dystopian elements weave their way into the story. The line between artifice and reality also makes an appearance in the form of the robot which the movie is best known for. This robot was created by Rotwang, a scientist who is in the service of the main character’s father – Joh Fredersen, the master of the city. Apparently, this robot is able to take human form and was created to replace his late wife. Once this robot was released into the city, she began sowing chaos amongst men who begin to lust after her, and is the very reason the workers began revolting in the first place. She even causes the character of Rotwang to go insane when he can no longer distinguish between the robot and the woman she’s impersonating.

Neuromancer/Sprawl Trilogy:

Gibson is one of the undisputed master’s of cyberpunk and future noire lit and it was this novel – Neuromancer – that started it all for him. In it, he coined the terms cyberspace, the matrix, and practically invented an entire genre of Gothic, techno-noire terminology which would go on to inspire several generations of writers. His work is often compared to Blade Runner given the similar focus on urban sprawl, cybernetic enhancements, the disparity between rich and poor, and the dark imagery it calls to mind.

Gibson is one of the undisputed master’s of cyberpunk and future noire lit and it was this novel – Neuromancer – that started it all for him. In it, he coined the terms cyberspace, the matrix, and practically invented an entire genre of Gothic, techno-noire terminology which would go on to inspire several generations of writers. His work is often compared to Blade Runner given the similar focus on urban sprawl, cybernetic enhancements, the disparity between rich and poor, and the dark imagery it calls to mind.

The first installment in the “Sprawl Trilogy”, this book takes place in the BAMA – the Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis (aka. The Sprawl). In this world of the 21st century, cyberspace jockeys or cowboys use their “decks” – i.e. consoles – to hack into corporate databases and steal information. The purpose is, as always, to sell off the information to the highest bidder, usually another corporate power. In addition, guerrilla tactics and domestic terrorism are often used to get employees out of their contracts, seeing as how most companies have no intention of ever letting their talent go!

The first installment in the “Sprawl Trilogy”, this book takes place in the BAMA – the Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis (aka. The Sprawl). In this world of the 21st century, cyberspace jockeys or cowboys use their “decks” – i.e. consoles – to hack into corporate databases and steal information. The purpose is, as always, to sell off the information to the highest bidder, usually another corporate power. In addition, guerrilla tactics and domestic terrorism are often used to get employees out of their contracts, seeing as how most companies have no intention of ever letting their talent go!

Also, there is the massive gulf that exists between the rich and the poor in these novels. Whereas the main characters tend to live in overcrowded tenements and dirty neighborhoods, the rich enjoy opulent conditions and control entire parts of the world. In addition, the richest clans, such as the Tessier-Ashpools and Vireks, actively use cloning and clinical immortality to cheat death, and often live in orbital colonies that they have exclusive rights to. Much like in his “Bigend Trilogy”, much attention is dedicated to the transformative power of wealth and how it affords one better access to the latest in technology.

But always, the focus is on the street. Here, jockeys, freelancers and Yakuza agents are at work, pulling jobs so they can buy themselves the latest enhancements and the newest gear. In the case of Molly Millions, a freelance lady-ninja, this includes razor nails that extend from her fingertips. In the case of Yakuza enforcer from the short-story (and movie) Johnny Mnemonic, it consists of a filament of monomolecular razor wire hidden inside his thumb. For others, it might consist of artificial limbs, new organs, implants of some kind. Whatever ya need, they got it in the Sprawl. If not, you go to Chiba City or Singapore, chances are it was made there anyway!

But always, the focus is on the street. Here, jockeys, freelancers and Yakuza agents are at work, pulling jobs so they can buy themselves the latest enhancements and the newest gear. In the case of Molly Millions, a freelance lady-ninja, this includes razor nails that extend from her fingertips. In the case of Yakuza enforcer from the short-story (and movie) Johnny Mnemonic, it consists of a filament of monomolecular razor wire hidden inside his thumb. For others, it might consist of artificial limbs, new organs, implants of some kind. Whatever ya need, they got it in the Sprawl. If not, you go to Chiba City or Singapore, chances are it was made there anyway!

*Interesting Fact: according to Gibson, Blade Runner came out when he was still tinkering with the manuscript for this novel. After seeing it, he nearly threw the manuscript out because he was afraid Ridley Scott had pre-empted him! Funny how things work out, huh?

Final Thoughts:

Gee, there really isn’t much more to say is there? One thing I have noticed is that much of modern dystopia comes to us in the form of the cyberpunk genre. Though the definition of cyberpunk appears to constantly be evolving, it is generally acknowledged that it is a postmodern form of science fiction that combines “high tech and low life.” Having sorted through several modern examples of dystopian sci-fi, I can say that this is certainly an apt description.

In essence, it assumed that the presence of high tech would entail the emergence of a dystopian society, that the endless march of progress would lead to the destruction of the environment, the devaluing of human life, the elimination of privacy, and the line between real and fake. This last aspect was especially important, embracing cybernetics, virtual reality, and things like cloning and clinical mortality. Since the 1980’s, all of these notions have infiltrated science fiction movies, television, and have even become cliches to some extent.

This genre has given rise to new kinds of science fiction as well. For example, it is generally acknowledged that a sub genre known as post-cyberpunk emerged in the 1990’s which broke away from its predecessor in one key respect. Whereas it too focused on the rise of technology, it did not anticipate dystopia as part of the process. This is best exemplified by books such as Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age, a 21st century bildungsroman which predicted vast social and political changes as a result of nanotechnology.

Other sub genres that have emerged in recent years include “Steampunk”, a literary form that combines Victorian era technologies with the punk genres noire sensibilities. Other derivatives include Dieselpunk, Nanopunk, Biopunk, and even fantasy-punk crossovers like Elfpunk. Yes, like most things in the post modern era, it seems that literary genres are becoming fragmented and tribalistic!

But alas, I still feel the need to ask the question, what’s happened to dystopian literature of late? In my initial post, I got a lot of people asking me if I could include some more modern examples. You know, stuff that’s come out since 1984 and The Handmaids Tale. But unfortunately, what I’ve found tends to be more of the same. Just about every example of dystopian fiction appears to draw its inspiration from such handy classics as the one’s I’ve already mentioned, or is in some way traceable to them. Does this mean that we’ve hit bottom on the whole genre, or could it just be we’ve moved away from it for the time being?

Well, I recently learned from an article on IO9 that Neal Stephenson himself stated that science fiction needed to stop being so pessimistic and had to start getting inspirational again. Perhaps he’s onto something… Maybe we’ve gone too far with the whole cautionary tale and need to steer things back towards a brighter future, urging people on with common sense and technological solutions rather than laments. Maybe we need to let them know that such problems as world hunger, overpopulation, pollution, climate change, poverty, war, licentiousness and greed can all be overcome.

Then again, I’m working on a couple dystopian tales right now… Is it too much to ask that this craze last just a few years longer?

Thanks to all who’ve written in and “liked” my dystopian series! Hope to see y’all again soon as I get into ore cheerful things…