Lately, I’ve been feeling kind of dystopian! Perhaps it’s the fact that I’m working on an anthology of dark science fiction with some fellow writer’s over at Goodreads (called Writer’s Worth). Or it might just be that this seemed like the next logical step in the whole “conceptual science fiction” thing. Regardless, when it comes to the future, sci-fi writers love to speculate, and it usually takes one of two forms. Either humanity lives in a utopian society, where technology, time, and evolution have ferreted out our various weaknesses. Or, we live in a dystopian world, where humanity has either brought itself to the brink of annihilation or is living in dark, polluted, and overpopulated environments, the result of excess and environmental degradation.

As with all things science fiction, the aim here is to use speculative worlds of the future to offer commentary on today. As William Gibson, himself a dark future writer, once said: “Science fiction [is] always about the period in which it was written.” So today, I thought I would acknowledge some truly classic examples of dystopian literature and the books that started it all. Here they are:

Earliest Examples

Dystopian literature, contrary to popular conception, did not begin in the 20th century with Brave New World. In fact, one can find examples going as far back as the Enlightenment when philosophers and scholars used fictional contexts to illustrate the weaknesses of society and how they might be reformed. And, in many ways, this form of social critique borrowed from Utopian literature, a genre that takes its name from Thomas More’s seminal book that describes a perfect fictional society.

But where More and earlier writers (such as Plato and St. Augustine) used perfect civilizations to parody contemporary society, this newer breed of authors used dark ones to do the same. In short, Utopian literature showed society how it could be, dystopian literature as it was.

Candide:

A true classic, though it is sometimes difficult to classify this work as a true dystopian work of fiction. For one, it is set in the contemporary world, not in a fictionalized society, and revolves around the life of a fictional character who travels from one region to the next, seeking to answer the fundamental question of whether or not this is “the best of all possible worlds”. However, this book remains one of the principal sources of inspiration for science fiction writers when constructing fictional worlds for the sake of satirizing their own.

Published in 1755 by the critic and philosopher Voltaire, the story was inspired by the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake and the church’s and Leibnizian’s attempts to rationalize it. At the beginning, Candide – the main character whose name means “optimism” – lives a sheltered existence where he is busy studying and living with his friends and companions. However, this existence is quickly interrupted by the arrival of war, and Candide and his companions are forced to travel from place to place, witnessing all the problems of the world.

These include war, slavery, rape, imperialism, abuse of power, and exploitation, which they observe as the story takes them from Europe to the Middle East to the Americas. Eventually, they return home and reflect on all they have seen and whether or not this is “the best of all possible worlds”. They conclude that it is not, but offer a resolution by saying that “we must cultivate our garden”.

Gulliver’s Travels:

Another classic example that is often considered a combination of utopian and dystopian novels. This is because the plot involves the travels of one man – Gulliver, whose name is a play on the world gullible – whose journey takes him through many fictional worlds where life is either perfect or tragically flawed in various ways. However, since the purpose of these worlds is to parody English society in his day, it is often included as an early example of satiric literature that falls into the utopian, dystopian, and science fiction camps.

The story involves four journeys where Gulliver travels to several fictional societies and records what he sees for posterity. The first voyage takes him to the land of the Lilliputians, a race of tiny people whose morals match their physical size. After some rather brief descriptions of how these people select their leaders (limbo tournaments and other stupid games), we learn that they are a parody of the British system of parliament.

His second voyage takes him to a place that is the polar opposite of the first. Here, in the land of the Brobdingnagians, he is presented with giants whose physical size mirrors their moral outlook. They consider Gulliver to be a curious specimen, whose descriptions of his country disgust them. In the end, they consider him a cute sideshow attraction and refuse his offer of technological advances (like gunpowder). Gulliver then leaves, thinking the people are out of their minds, but ironically states that he withheld the worse about England out of a desire to save face.

His next voyage involves a little “island-hopping”, first to the flying city of Laputa, an island nation where technological pursuits are followed without a single regard for the consequences. He then detours to another island, Glubbdubdrib, where he visits a magician’s dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures.

Then onto Luggnagg, where he encounters the struldbrugs – an unfortunate race of people who are immortal but frozen in old age, with all the infirmities that come with it. Gulliver then reaches Japan, which is in the grips of the post-war Shogunate period, where he is narrowly excused from taking part in an anti-Christian display that all foreigners were forced to perform at the time (stepping on the symbol of the Cross).

His final voyage before going home takes him country of the Houyhnhnms, a race of horse-people who see themselves as “the perfection of nature” and who rule over the race of Yahoos – deformed humans who exist in their basest form. Gulliver joins them and comes to adopt their view of humanity – that of base creatures that use reason only to advance their own appetites. However, they soon come to see him as a Yahoo and expel him from their civilization. In the end, Gulliver returns home to regal his family of his adventures but finds that he cannot relate to them anymore. His journeys have filled him with a sense of misanthropy that he cannot ignore.

Throughout the narrative, Swift’s point seems abundantly clear. Each voyage to a fictitious world serves as a means to parody a different element of British society and civilization in general. And ultimately, Gulliver serves as the perfect narrator, in that his ignorance and naivety allow him to absorb the lessons of the journey in a way that is both ironic and sufficiently detached. Can’t just hand the reader the moral, after all! Gotta make them work for it!

The Time Machine:

Published in 1895, this science fiction novella inspired countless adaptations and popularized the very idea of time travel. In addition to introducing readers to the concept of time as the fourth dimension and temporal paradoxes, H.G. Wells also had some interesting social commentary to share. In this story, the narrator – known only as The Traveller – recounts to a bunch of dinner guests how he used a time machine to travel to the year 802, 701 A.D. where he witnessed a strange culture made up of two distinct peoples.

On the one hand, there were the Eloi, a society of elegant, beautiful people who live in futuristic (but deteriorating) buildings and do no work. Attempts to communicate with them prove difficult since they seem to possess no innate curiosity or discipline. He assumes that they are a communistic society who have used technology to conquer nature and evolved (or devolved) to a point where strength and intellect are no longer necessary to survive.

However, this changes when he comes face to face with a separate race of ape-like troglodytes who live in underground enclaves and surface only at night. Within their dwellings, he discovers the machinery and industry that makes the above-ground paradise possible. He then realizes that the human race has evolved into two species: the leisured class of the ineffectual Eloi, and the downtrodden working classes that have devolved into the brutish Morlocks. In the course of searching the Morlock enclave, he learns that they also feed on the Eloi from time to time. His revised analysis is that their relationship is not a benign one, but one characterized by animosity and the occasional act of kidnapping and cannibalism.

Is there not a more perfect vision of industrial society or class conflict? Written within the context of turn of the century England, where discrepancies in wealth, class conflict, and demands for reform were commonplace, this book was clearly intended to explore social models in addition to scientific ideas. And the commentary was quite effective if you ask me…

The Iron Heel:

This dystopian work was written by Jack London, the same man who wrote the classic Call of the Wild, and was released in 1908. A clear expression of London’s own socialist beliefs, the novel is set in the distant future when a socialist utopia – known as the Brotherhood of Man – has finally been created. Overall, the plot revolves around the “Everhard Manuscript”, a testament that details the lives of the story’s two main protagonists and which takes place between 1912 to 1932 in the US. The work is known for its big “spoiler”, letting readers know outright that the protagonists die in the course of their pursuits, but that their efforts are rewarded by providing inspiration to later generations who succeed where they fail.

In the course of this speculative story, we learn that an oligarchy – the Oligarchs or “Iron Heel” – has seized power in the US by bankrupting the middle class and reducing farmers to a state of serfdom. Once in power, they maintained order through a combination of preferential treatment and control over the military. After a failed revolt (the First Revolt) takes place, preparations are underway for a second which is expected to succeed in restoring the Republic. Unfortunately, it too fails and the protagonists are killed. However, centuries later, when their Manuscript is discovered, the Oligarchy has been unseated and a debt is being acknowledged to these characters and their actions.

Thus, London speculates that a socialist society would someday emerge in the US, but only after centuries of dominance by oligarchs who would come to power by decimating the middle class, controlling trade unions, and transforming the military into a mercenary front. His main characters, though condemned to death in the present, will be vindicated in the distant future when humanity will, at last, overcome its greedy tendencies and usher in a state based on equality and fraternity. Apparently, this novel inspired such greats as George Orwell, but not in the way you think. Whereas London chose to offer his readers a sense of consolation by showing them everything turned out okay in the distant future, Orwell chose to take the hopeless route to make his point!

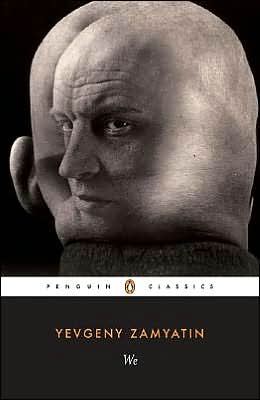

We:

The story takes place in the distant future, roughly one thousand years after the One State conquered the entire world. After years of living in a perfectly synchronized, rational, and orderly world, the people of the One State are busy constructing a ship (the Integral) that will export their way of life to extra-terrestrial worlds. Published in 1921, and written by Yevgeny Zamyatin, the story was clearly inspired by life in post-revolutionary Russia, with its commitment to “scientific Marxism, but was also a commentary on the deification of reason at the expense of feeling and emotion.

The story is told from the point of view of D-503, chief engineer of the Integral who is keeping a journal which he intends to be taken on the voyage. As we learn in the course of the novel, everyone in the One State lives in glass apartments that are monitored by secret police known as the Bureau of Guardians. All sex is conducted strictly for reproductive purposes and cannot be done without state sanction. However, the main character soon comes into contact with a woman named I-330, a liberated woman who flirts with him, smokes, and drinks alcohol without regard for the law.

In time, he learns that I-330 is a member of a revolutionary order known as MEPHI which is committed to bringing down the One State. While accompanying her to the Ancient House, a building notable for being the only opaque structure in the One State where objects of historic and aesthetic importance are preserved, he is escorted through a series of tunnels to the world outside the Green Wall which surrounds the city-state. There, D-503 meets the inhabitants of the outside world – humans whose bodies are covered with animal fur. The aim of the MEPHI is to destroy the Green Wall and reunite the citizens of the One State with the outside world.

In his last entry, D-503 relates that he has undergone an operation that is mandated for all citizens of the One State. Similar to a lobotomy, this operation involved targeted x-rays that eliminate all emotion and imagination from the human brain. Afterward, D-503 informs on I-330 and MEPHI but is surprised how she refuses to inform on her compatriots once she is captured. People beyond the wall even succeed toward the story’s end in breaching a part of the Green Wall, thus ending the story on an uncertain note.

The Classics

And now we move on to the dystopian classics that are most widely known, that have inspired the most adaptations and sub-genres of noir fiction. Although updated many times over for the 20th century, these dystopian novels share many characteristics with their predecessors. In addition to timeless social commentary, they also asked the difficult question of what it would take to set humanity free.

Whereas some chose to confront this question directly and offer resolutions, other authors chose to leave the question open or chose to offer nothing in the way of consolation. Perhaps they thought their stories more educational this way, or perhaps they could merely think of none. Who’s to say? All I know is their works were inspired!

In addition to parodying the worst aspects of scientific rationalism, imperialism and the notion of progress, the story also went on to inspire some of the greatest satires ever known. In addition, many of its more esoteric elements have appeared in countless novels and films over the years, most notably the concepts of encapsulating walls, secret museums, government-sanctioned breeding, and machine-based programming.

Brave New World:

There’s scarcely a high school student who hasn’t read this famous work of dystopian fiction! And although Aldous Huxley denied ever reading We, his novel nevertheless shared several elements with it. For instance, his story was set in the World State where all reproduction is carried out through a system of eugenics. In addition, several “Savage Reservations” exist beyond the veil of civilization, where people live a dirty, natural existence. But ultimately, Huxley’s aim was to comment on American and Western civilization of the early 20th century, a civilization where leisure and enjoyment were becoming the dominant means of social control.

This last aspect was the overwhelming focus of the novel. In the World State, all people are bred for specific roles. Alphas are the intellectuals and leaders of society, Betas handle high-level bureaucratic tasks, Deltas handle skilled labor, Gammas unskilled labor, and Epsilons menial tasks. Therefore, all vestiges of class conflict and generational conflict have been eliminated from society.

But to further ensure social control, all citizens are sleep-conditioned from a young age to obey the World State and follow its rules. These include the use of Soma, a perfectly legal and safe designer drug that cures all emotional ales, promiscuous sex habits, and “feelies” (movies that simulate sensation).

In the end, the story comes to a climax as two of the main characters, Bernard Marx and Lina Crowe, go to a savage reservation and find a lost child named John. His mother was apparently a citizen of the World State who became lost in the reservation and was forced to stay after she learned she was pregnant. Having experienced nothing but alienation and abuse as a “savage”, John agrees to go with Bernard and Lina back to “civilization.

However, he quickly realizes he doesn’t fit into their world either and expresses disdain for its excesses and controls. Eventually, the people who sympathize with him are sent into exile and he is forced to flee himself. But in the end, he finds that he cannot escape the people of the World State and commits suicide, a tragic act that symbolizes the inability of the individual to find a resolution between insanity and barbarity.

Overall, Huxley’s BNW was a commentary on a number of scientific developments which, under the right circumstances, could be used to deprive humanity of their freedom. In many ways, this was a commentary on how the expanding fields of psychology and the social sciences were being used to find ways to ensure the cooperation of citizens and ensure good work habits.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in factories and in the creation of “assembly-line discipline”, which was exemplified by how the people of the World State revered Henry Ford. In addition to performing eugenics on an assembly-line apparatus, the people worship Ford and cross themselves with a T (a reference to his model T car).

But above all, Huxley seemed to be asking the larger question of what is to be done about the process we know as civilization. If it was inimical to freedom, with all its rational, sterile, and domesticated luggage, and the alternative – a dirty, superstitious, and painful existence – was not preferable either, then what was the solution?

In the end, he offered no solution, allowing the reader to ponder this themselves. In his follow-up essay, Brave New World Revisited, he expressed some remorse over this fact and claimed that he wished he had offered a third option in the form of the exile communities – people who had found their own way through enlightened moderation.

1984:

Ah yes, the book that did it all! It warned us of the future, taught us the terminology of tyranny, and educated us on the use of “newspeak”, “doublethink” and “thoughtcrime”. Where would dystopian literature be today were it not for George Orwell and his massively influential satire on totalitarianism? True, Orwell’s work was entirely original; in fact, he thoroughly acknowledged a debt to authors like H.G. Wells and Yevgeny Zamyatin. But it was how he synthesized the various elements of dystopia, combining them with his own original thoughts and observations, and crystallized it all so coherently that led to his popularity.

But I digress. Set in the not-too-distant future of 1984 (Orwell completed the book in 48 and supposedly just flipped the digits), the story takes place from the point of view of an Outer Party member named Winston Smith. Winston lives in London, in a time when England has been renamed Airstrip One and is part of a major state known as Oceania. As the book opens, Oceania finds itself at war with the rival state of Eurasia, though not long ago it was at war with Eastasia and will be so again. As a member of the Ministry of Truth, Winston’s job is that of a censor. Whenever the enemy changes, whenever the Party alters its policies, whenever a person disappears, or the Party just feels the need to rewrite something about the past, men like Winston are charged with destroying and altering documentation to make it fit.

Ultimately, the story involves Winston’s own quest for truth. Living in the constant, shifting lie that is life in the totalitarian state of Oceania, he seeks knowledge of how life was before the revolution; before the Party took control before objective reality become meaningless. He also meets a woman named Julia with whom he begins an affair and rediscovers love.

However, in time the two are captured and taken to the Ministry of Love, where they are tortured, brainwashed, and made to turn on each other. In the end, Winston accepts the Party’s version of reality, simply because he discovers he has no choice. His tragic end is made all the more tragic by the implicit knowledge that he will soon be killed as well.

For discerning fans of science fiction and dystopian literature, the brilliance of 1984 was not so much in how the totalitarian state of the future is run but how it came to be. According to the Goldstein Manifesto, which is the centerpiece of the novel, World War III took place sometime in the 1950s and ended in a stalemate, all sides having become convinced of the futility of nuclear war.

Shortly thereafter, totalitarian revolutionaries with similar ideologies took power all over the planet. In time, they became the three major states of Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia, whose boundaries were a natural extension of the post-war spheres of influence.

Also interesting is Orwell’s speculation on how these totalitarian ideologies came to be in the first place. In short, he speculates that dominance by a small group of elites has been an unbroken pattern in human history. In the past, this arrangement seemed natural, even somewhat desirable due to poverty, scarcity, and a general lack of education.

However, it was within the context of the 20th century, at a time when industrial technology and availability of resources had virtually eliminated the need for social distinction, that the most vehement totalitarians had emerged. Unlike the elites of the past, these ones had no illusions about their aims or their methods. As the antagonist, O’Brien, says “The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake… Power is not a means; it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.”

This message still resonates with us today. Even though western civilization did technically dodge the bullet of WWIII and does not resemble the world of 1984 in the strictest sense, the cautionary nature of Orwell’s critique remains. Even if the particulars of how 1984 came to be didn’t happen, the message remains the same: human freedom – meaning the freedom to live, love, and think freely – is the most precious thing we have. Beware those who would deprive you of it for your own safety or in exchange for some earthly utopia, for surely they will themselves to be your master! There is also an ongoing debate about which came true, 1984 or BNW, with the consensus being that it was Huxley’s dystopian vision that seemed more accurate. However, the jury is still out, and the debate is ongoing…

Fahrenheit 451:

Here is yet another dystopian novel that has become somewhat of a staple in the industry. In Bradbury’s vision of the future, society is permeated by mindless leisure and decadence. Virtually all forms of literature have been banned, and local “firemen” are responsible for enforcing the ban. Wherever illegal literature is found, firemen are responsible for arriving on the scene and putting them to the flame. Yes, in a world where all houses are fireproof, firemen are no longer responsible for putting fires out, but for starting them!

In the course of the story, the main character – a fireman named Guy Montag – begins to become intrigued with literature and discovers a sort of magic within it that is missing from his world. In addition, Guy is told by his boss that society became this way willingly. Perhaps out of fear, perhaps out of sloth, they chose convenience, ease, and gratuity over subtly, thought and reflection. In time, Guy’s choices make him a fugitive and he is forced to flee and seek refuge with other people who insist on keeping and reading books. It is also made clear that nuclear war is looming, which may provide some explanation as to how society came to be the way it is.

In this way, the book has a lot in common with both 1984 and Brave New World. On the one hand, there is active censorship and repression through the destruction of books and the criminalization of reading. On the other hand, it seems as though the people in Bradbury’s world surrendered these freedoms willingly. It is a fitting commentary on American society of the latter half of the 20th century, where entertainment and convenience seemed like the greatest threats to independent thought and learning. This, in turn, could easily form the basis of dictatorship. As we all know, a docile, narcotized society is an easily controlled one!

The Handmaid’s Tale:

Here is another novel that few people get through high school without being forced to read, especially in Canada. But there’s a reason for that. Much like 1984, BNW, and F451, The Handmaid’s Tale is a classical dystopian narrative that has remained relevant despite the passage of time. In this story, the US has been dissolved and replaced by a theocracy known as the Republic of Gilead. In this state, women have been stripped of all rights in accordance with Old Testament and Christian theocracy. The head of this state is known as the Commander, the chief religious-military officer of the state.

The story is told from the point of view of a handmaid, a woman whose sole purpose is to breed with the ruling class. Her name is Offred, which is a patronym of “Of Fred”, in honor of the man she serves. Like all handmaidens, her worth is determined by her ability to procreate. And on this, her third assignment, she must get pregnant if she doesn’t want to be discarded. This time around, her assignment is to the Commander himself, a man who quickly becomes infatuated with her.

Over time, the infatuation leads to sex that is done as much for pleasure as procreation, and he begins to expose her to aspects of culture that have long been outlawed (like fashion magazines, cosmetics, and reading). She even learns of a Mayday resistance that is concerned with overthrowing Gilead, and that the Commander’s driver is apparently a member.

In the end, Offred is denounced by the Commander’s wife when she learns of their “affair”. Nick orders men from “The Eyes” (i.e. secret police) to come and take her away. However, he privately intimates that these are actually men from the resistance who are going to take her to freedom. The story ends with Offred stepping into the van, unsure of what her fate will be. In an epilogue, we learn that the story we have been told is a collection of tapes that were discovered many generations later after Gilead fell and a new, more equal society re-emerged. This collection is being presented by academics at a lecture, and is known as “The Handmaid’s Tale”.

In addition to touching on the key issues of reproductive rights, feminism, and totalitarianism, The Handmaid’s Tale presents readers with the age-old scenario of the rise of a dictatorship in the US. Apparently, the military-theological forces who run Gilead in the future seized power shortly after a staged terrorist attack that was blamed on Islamic terrorists. In the name of restoring order and ending the decline of their country, the “Sons of Jacob” seized power and disbanded the constitution. Under the twin guises of nationalism and religious orthodoxy, the new rulers rebuilt society along the lines of Old Testament-inspired social and religious orthodoxy.

This angle is not only plausible but historically relevant. For as Sinclair Lewis said back in 1936 “When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.” This is paraphrased from his actual, more lengthy comments. But his essential point is the same. If a tyranny emerged in the US, he reasoned, it would do so by insisting that it was religiously right and that it was intent on protecting people’s freedoms, not revoking them.

In addition, the angle where an Islamic terrorist attack spawned the takeover? Tell me that’s not relevant to Americans today! Though written in 1985, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian scenario received a shot of credibility thanks to eight years of the Bush administration, a government that claimed religious orthodoxy and used security as justification for questionable wars and many repressive policies.

Final Thoughts:

After years of reading dystopian literature, I have begun to notice certain things. For starters, it is clear why they are grouped with science fiction. In all cases, they are set in alternate universes or distant future scenarios, but the point is to offer commentary on the world of today. And in the end, utopian and dystopian satires are inextricably linked, even if the former predates the latter by several centuries.

Whereas Utopian literature was clearly meant to offer a better world as a foil for the world the writers were living, dystopian literature offers up a dark future as a warning. And in each case, these worlds very much resemble our own, the only real difference being a matter of degree or a catalyzing event. This is why there is a focus in dystopian literature on explanations of how things came to be the way they are. In many cases, this would involve a series of predictable events: WWIII, a terrorist attack, more overpopulation and pollution, an economic crisis, or a natural disaster.

And in the end, the message is clear: whether it is by fear, poverty, or the manipulation of critical circumstances, power is handed over to people who will deliberately abuse it. Their mandate is clear and their outlook is the exact same as any tyrant who has ever existed. But the important thing to note is that it is given. Never in dystopian literature do tyrants simply take power. Much like in real life, true totalitarianism in these novels depends upon the willingness of people to exchange their freedom for food, safety, or stability. And in all cases, they inevitably experience buyer’s remorse!

Quicknote: Since getting “freshly pressed”, a lot of people have written in and asked me about my thoughts on “The Hunger Games”. Sorry to say, haven’t read it so I can’t offer any commentary. I will however be commenting on a number of more modern dystopian franchises, specifically examples found in film and other media, in my next post. Stay tuned, hopefully, something you like will pop there!