Many months ago, I was struck by an idea. It is one which has been percolating in my mind for some time, but never really occurred to me as a reason to write. But then, I began to get into the whole “Alternate History” sub-genre of science fiction, examining such works as The Man In The High Castle, Fatherland, The Guns Of The South, and A Rebel In Time. It made me think that there was a good precedent for this kind of idea, and room for expansion.

Many months ago, I was struck by an idea. It is one which has been percolating in my mind for some time, but never really occurred to me as a reason to write. But then, I began to get into the whole “Alternate History” sub-genre of science fiction, examining such works as The Man In The High Castle, Fatherland, The Guns Of The South, and A Rebel In Time. It made me think that there was a good precedent for this kind of idea, and room for expansion.

But first, let me explain what I was thinking. Ever since University I’ve been fascinated by Russian history, particularly the interwar years. It was at this time that the most auspicious achievements and crimes took place in the former Soviet Union, after the death of Lenin and the ascent to power of Joseph Stalin, one of history’s greatest monsters.

Shortly thereafter, Russia became involved in World War II, during which time another monster – Adolf Hitler – committed unspeakable crimes against the Russian people. Over twenty six million people died on the Eastern Front, most of them civilians who had already witnessed such terrible suffering at the hands of their own dictator. In addition, many were victims of Soviet wartime oppression, killed by Stalin for the crime of not fighting hard enough or attempting to find liberation from their Nazi invaders.

From the point of view of Soviet propaganda, the years between 41 and 45 were portrayed as a the “Great Patriotic War”, a heroic struggle for the defense of the Motherland. In some respects this was true, but mainly it was a war between two nations being led by very petty and cynical men, with countless good and innocent souls caught in between. Those Germans who died in the East did so because of a fool’s dream of Lebensraum and racial purity, whereas the Russians who died did so in the defense of their families from both the invaders and the reprisals of NKVD officers.

Reading of all this, I often wondered, what if Leon Trotsky, Lenin’s intended successor, had led Russia during the interwar years? What if he had won the leadership race, instead of the scheming Stalin, and became the man to lead Russia against the Nazi invaders? Would things have worked out differently? Would Russia have still stood and ground up the Nazis, but in a way that didn’t lead to the death of so many millions of innocent Russians. The question is not a new one. In fact, historians have been pondering it for some time, and the entire question hinges on a single event.

This is where the concept of my own alternate history came in. In my story, a single event happens differently, thus giving rise to an alternate history. At the 13th Party Congress in Russia 1924, Trotsky had an historic opportunity. Lenin, before his death, had published his “Last Will And Testament” where, amongst other things, he singled out Stalin as a rude and ruthless character who should never be allowed to come to power. During the years following Lenin’s death, Trotsky was seen as the natural successor, which made him the natural rival of Stalin and his followers.

During the 12th Party Congress, Stalin’s allies helped suppress news of the Testament, but by the 13th, Trotsky was in possession of it and could released it, causing irreparable harm to Stalin’s reputation. Why he did not, and instead chose to make a conciliatory speech calling for unity, is something which historians have debated ever since. In so doing, he essentially guaranteed Stalin’s rise to power and his own exile, which culminated in his murder in Mexico some years later.

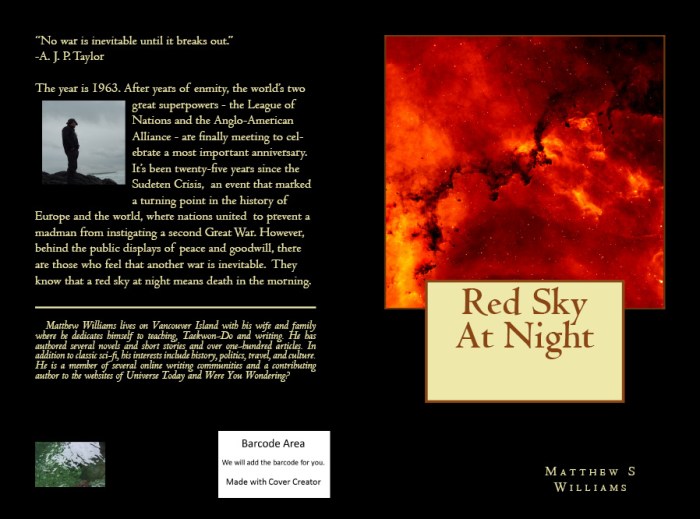

Red Sky At Night:

This is the basis of my idea. Instead of asking for reconciliation, Trotsky released Lenin’s Testament to the Party and asked for Stalin’s removal. He was successful, which guaranteed that it was he who would become the new leader of Soviet Russia and its chief planner during the interwar years. As a result, Stalin’s crash industrialization programs (aka. the Five Year Plans) were never launched.

This is the basis of my idea. Instead of asking for reconciliation, Trotsky released Lenin’s Testament to the Party and asked for Stalin’s removal. He was successful, which guaranteed that it was he who would become the new leader of Soviet Russia and its chief planner during the interwar years. As a result, Stalin’s crash industrialization programs (aka. the Five Year Plans) were never launched.

Instead, he maintained Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) and even appointed Bukharin (whom Stalin murdered) to oversee reform and expansion of state-owned industry. This led to a degree of slow recovery for the Soviet economy and improved the lot of its farmers and small private enterprises. And when the Great Depression hit in 1929, Russia would still spared the worst ravages of it while similarly showing signs of growth.

What’s more, Trotsky maintained close ties to foreign communist movements, rather than focusing so heavily on matters at home. As a result, in 1933 when the Nazis demanded a non-confidence vote against the Social Democratic Party, Trotsky ordered the KDP (Communist Party of Germany) to stand shoulder to shoulder with the Social Democrats, a move which did not alter the Nazi seizure of power, but which ensured that they were aligned with the anti-Nazi movement from early on.

In China, rather than advising Mao to go along with the Nationalist government (which turned on them) Trotsky advised that Mao and his cadres remain committed to resisting Japanese invasion and not trusting in Chiang Kai Shek. This prevented the massacre of Chinese Communists, which came in handy when the Sino-Japanese war began in 1937.

When the Spanish Civil War began, Trotsky and the Comintern became the most vocal and committed supporters of the Loyalists, sending them weapons, advisers, volunteers and funds. Much as in our own timeline, this had the effect of making the Soviets look like the chief supporters of anti-fascism, but since the effort didn’t suffer from Stalin’s paranoia and cynicism, the efforts were much more effective and popular. And thanks to Trotsky’s focus on foreign affairs, Commissar Maxim Litvinov, the champion of Collective Security, received the support he needed when he made his pitches to the League of Nations.

When the Spanish Civil War began, Trotsky and the Comintern became the most vocal and committed supporters of the Loyalists, sending them weapons, advisers, volunteers and funds. Much as in our own timeline, this had the effect of making the Soviets look like the chief supporters of anti-fascism, but since the effort didn’t suffer from Stalin’s paranoia and cynicism, the efforts were much more effective and popular. And thanks to Trotsky’s focus on foreign affairs, Commissar Maxim Litvinov, the champion of Collective Security, received the support he needed when he made his pitches to the League of Nations.

But most importantly of all, no purges or Great Terror took place during the late 30’s, which had the effect of undermining Russia’s efforts abroad, embarrassing Russia politically, decimating the Soviet officer corps, and devastating Russia’s agriculture. Russia therefore was in a much better position to coordinate alliances with the Czechs, the French, and rally public opinion towards ensuring that the Nazis were contained rather than appeased.

However, things really came down to the 1938 Sudetenland Crisis. For years, the Russians had been railing against coming to an accommodation with Hitler, largely for their own purposes. However, when Hitler demanded that Prime Minister Benes of Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland under threat of war, things finally came together for them. Facing harsh public opinion, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain found that he had little support for his policy of appeasement. French, Czech and League opinion were similarly opposed to any deal with Hitler, having been empowered by Russia’s example. As a result, instead of demanding that Benes give Hitler what he wanted, England and France instead demanded that Poland and Romania agree to allow Russian troops to pass their territory to mobilize against Germany, should the need arise.

These efforts did not materialize, but the appearance of unity on behalf of the League gave Hitler pause. His Generals advised that he back down, facing the likely prospect of war on all fronts, and Hitler was forced to concede. Afterward, Germany suffered from renewed economic problems, and Hitler lost virtually all support. The Nazis fell from power, World War II did not happen, the Holocaust never occurred, and the post-war division of the world between two superpowers not happen.

In the East, Japan found itself trapped as the League closed in to issue economic sanctions and demand that it withdraw from China. Soon, the Japanese Imperial government fell as well, and the threat of war was neutralized. In Italy and Spain, Mussolini and Franco remained in power, but were sure to behave themselves and even rejoined the League of Nations. And of course, Mao and his cadres did not seize power in the immediate post-war years, but instead came to an accommodation with the Nationalists, forming a powerful bloc within the government.

In the East, Japan found itself trapped as the League closed in to issue economic sanctions and demand that it withdraw from China. Soon, the Japanese Imperial government fell as well, and the threat of war was neutralized. In Italy and Spain, Mussolini and Franco remained in power, but were sure to behave themselves and even rejoined the League of Nations. And of course, Mao and his cadres did not seize power in the immediate post-war years, but instead came to an accommodation with the Nationalists, forming a powerful bloc within the government.

However, there was a downside to all of this as well. For starters, the economic boom caused by the war did not happen. Instead, the global economy recovered slowly throughout the 1940’s and 50’s. What’s more, the accommodation that took place between Russia and mainland Europe after the war, which saw the election of Social Democratic parties in every country and the de-radicalizing of Soviet power at home, caused a rift to form between the Anglo-American world and Eurasia. By 1950, fearing socialist revolution at home, England and America withdrew from the League and formed their own bloc, the Anglo-American Alliance.

Towards the end of the 1950’s, relations began to worsen, as the Alliance condemned what they saw as attempts at subversion in their own sphere while the League condemned the persecution of dissidents and revolutionaries. Both sides became retrenched and a new arms race began, the League and the Alliance scrambling to recruit the best and brightest minds to help them create new and better weapons. By the end of the 1950’s, scientists on both sides of the Atlantic were close to creating the first atomic weapons.

Towards the end of the 1950’s, relations began to worsen, as the Alliance condemned what they saw as attempts at subversion in their own sphere while the League condemned the persecution of dissidents and revolutionaries. Both sides became retrenched and a new arms race began, the League and the Alliance scrambling to recruit the best and brightest minds to help them create new and better weapons. By the end of the 1950’s, scientists on both sides of the Atlantic were close to creating the first atomic weapons.

This is where the story opens. It’s 1963, twenty-five years since the Sudetenland Crisis took place, and the world is putting aside its difference to mark the occasion. East and West are coming together in a series of festivals, diplomatic summits, and tourist expos. However, behind the happy veneer of entente, the usual preparations for war continue. And in time, a series of events will trigger a crisis that could very well lead to another war. Much like in 1914, the world is sitting on a powder keg, and all that’s needed for another Great War to take place is for someone to provide the spark.

This idea got back-benched with my coming to join Writer’s Worth and all our anthology work, but I want to pick it back up. Much like Fascio Ardens (that’s its new title), I’m in the mood to write some genuine alternate history. It requires some staggering research to make these kinds of speculative works seem authentic and plausible, but I want to make it work. Call me crazy, especially since I’ve got it in my head to tackle two separate ideas. But as my grandpa used to say, “Lord hates a coward!”